Exposing Kraut Daddy’s Contradictions on X.

Published by @greywarden100

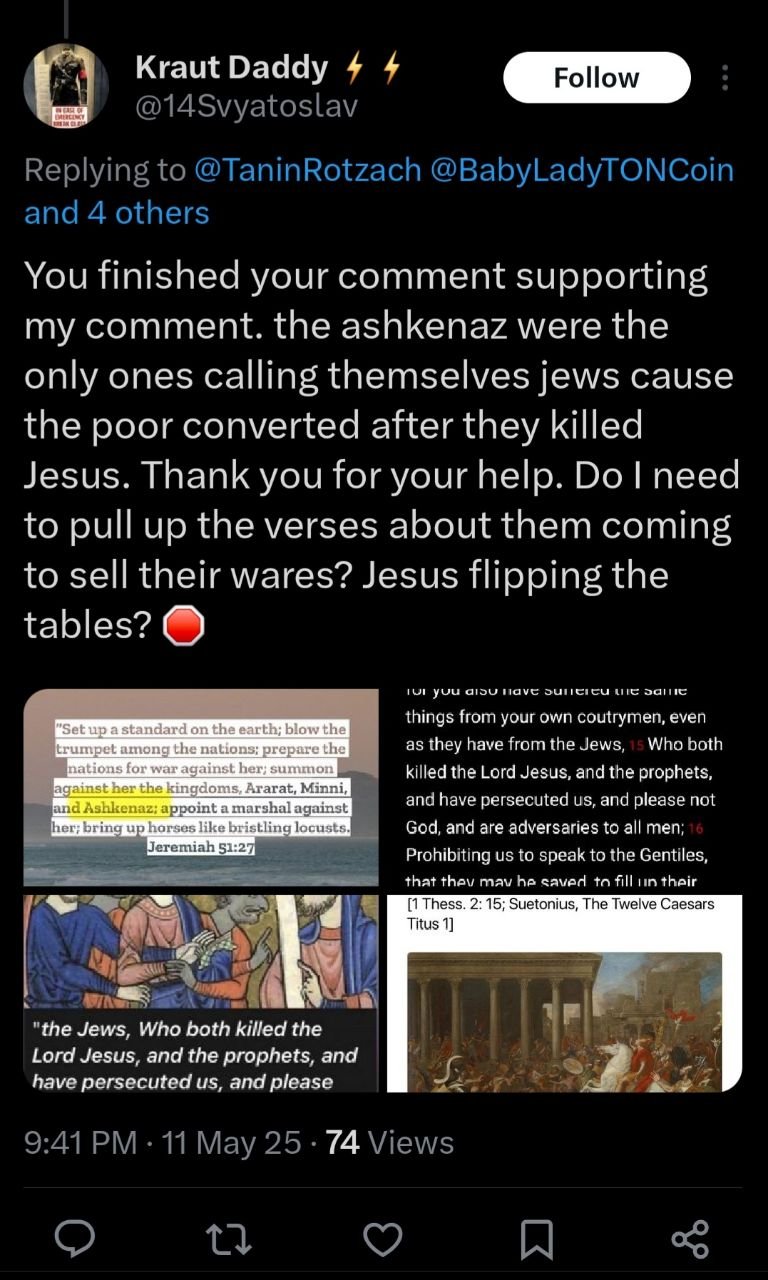

Kraut Daddy, an X user known for controversial posts, has repeatedly made inconsistent and contradictory claims about Ashkenazi Jews and their historical origins, often blending debunked theories with misinterpretations of biblical texts. This blog examines Kraut Daddy’s assertions, focusing on two major contradictions: his conflation of first-century Judean money changers with Ashkenazi Jews and his promotion of the discredited Khazar hypothesis while simultaneously linking Ashkenazi Jews to Middle Eastern populations. These inconsistencies reveal a pattern of historical and textual distortion, undermining his credibility. Below, we dissect these claims and provide evidence to refute them, drawing on genetic studies, biblical scholarship, and Kraut Daddy’s own posts.

I want to clarify that no Johns Hopkins study claims Ashkenazi Jews have 97.7% no ties to the Levant. This is a complete fabrication by Kraut Daddy. Johns Hopkins genetic research indicates Ashkenazi Jews have 46-50% Middle Eastern (Levantine) ancestry, not Turkic. Source: my X reply here: https://x.com/TaninRotzach/status/1931185478297874512?t=j5FaFStsPthtUaj2YDjZqw&s=19

Contradiction 1: Conflating First-Century Judean Money Changers with Ashkenazi Jews

Kraut Daddy claims that the “money changers” Jesus opposed in the Temple cleansing (Matthew 21:12–13, Mark 11:15–17, John 2:13–16) were not only Judeans of the first century but also directly connected to modern Ashkenazi Jews. He further asserts that these money changers engaged in lending and usury, practices he alleges continued through history under different names, ultimately identifying them as Ashkenazi Jews. This claim is problematic for several reasons.

Biblical Misrepresentation: As detailed in the blogs Refuting @14Svyatoslav’s Claims: Kollybistēs and the Temple Cleansing in Biblical Context and Addressing Misconceptions About the Temple Money Changers: A Response to @14Svyatoslav (available on Ecency), the Greek term kollybistēs used in the New Testament refers to money changers who exchanged currencies for Temple offerings, not lenders or usurers. The biblical texts do not mention lending or usury in this context; instead, they describe Jesus’ objection to commercial activity in the Temple’s sacred space. Kraut Daddy’s assumption of usury is an anachronistic imposition of later economic practices onto a first-century setting, unsupported by the text. These blogs thoroughly debunk his claims by analyzing the historical and linguistic context of the Temple incident.

Historical Anachronism: Kraut Daddy’s assertion that these first-century Judean money changers were Ashkenazi Jews is a glaring anachronism. Ashkenazi Jews, as a distinct ethnoreligious group, emerged in medieval Europe (circa 8th–10th centuries CE), nearly a millennium after the Temple cleansing (circa 30 CE). The Judeans of Jesus’ time were a diverse group of Jews living in the Levant, with no connection to the Ashkenazi population, which formed through migrations and admixture in Europe. By claiming these money changers were Ashkenazi, Kraut Daddy collapses centuries of history, ignoring the distinct origins and development of Ashkenazi Jewry.

Kraut Daddy’s Own Words: In one X post, Kraut Daddy states that the “same people” (money changers) have “gone by different names” throughout history, explicitly calling them “Ashkenazis.” This contradicts the historical record, as Ashkenazi Jews did not exist in the first century and can not be equated with Judean money changers. His attempt to draw a continuous line from biblical Judea to modern Ashkenazi Jews is baseless and reveals a lack of understanding of Jewish ethnogenesis.

Contradiction 2: Promoting the Khazar Myth While Acknowledging Middle Eastern Ties

Kraut Daddy’s most significant contradiction lies in his simultaneous endorsement of the Khazar hypothesis and his acknowledgment of Ashkenazi ties to the Middle East. The Khazar hypothesis, often called the “Khazar myth” by scholars, posits that Ashkenazi Jews are primarily descended from Turkic Khazars who converted to Judaism in the 8th–9th centuries CE and have no significant Middle Eastern ancestry. Kraut Daddy frequently promotes this debunked theory, aligning it with Marxist critiques to frame Ashkenazi Jews as “fake Jews” with no historical connection to the Levant. Yet, in his posts about the Temple money changers, he paradoxically links Ashkenazi Jews to Middle Eastern populations, contradicting his own narrative.

The Khazar Hypothesis Debunked: The Khazar hypothesis has been thoroughly discredited by genetic, linguistic, and historical evidence. Major DNA studies, as outlined in my previous response, demonstrate that Ashkenazi Jews have substantial Levantine ancestry (40–70%), with the remainder primarily European (Southern European in particular). Key studies include:

- Waldman et al. (2022, Cell): Ancient DNA from 14th-century Ashkenazi Jews in Erfurt, Germany, shows 19–43% Levantine ancestry, confirming genetic continuity with modern Ashkenazi Jews.

- Carmi et al. (2014, Nature Communications): Estimated 46–50% Middle Eastern ancestry in Ashkenazi Jews, with no significant Turkic or Khazar contribution.

- Behar et al. (2010, Nature): Found Ashkenazi Jews cluster closely with Levantine populations, with 50–70% Middle Eastern ancestry.

- Atzmon et al. (2010, American Journal of Human Genetics): Confirmed 30–60% Levantine ancestry, with no evidence of significant Caucasus or Turkic origins.

These studies, among others, show no significant genetic signal from the Caucasus or Central Asia, where the Khazars lived. Linguistic evidence further undermines the hypothesis: Yiddish, the historical language of Ashkenazi Jews, is primarily Germanic with Hebrew and Aramaic influences, showing no Turkic elements. Cultural evidence, such as Ashkenazi names, traditions, and customs, also lacks Turkic influence.

Kraut Daddy’s Contradiction: Despite promoting the Khazar myth, Kraut Daddy acknowledges the Middle Eastern context of the Temple money changers and calls them “Ashkenazis,” implying a connection to the Levant. This contradicts his claim that Ashkenazi Jews are solely Turkic Khazars with no Middle Eastern ties. For example, in one X post, he states that the “money changers” were part of a group that persisted in the Middle East, later becoming Ashkenazi Jews. This directly undermines his Khazar narrative, as it inadvertently affirms a Middle Eastern origin for Ashkenazi Jews, aligning with genetic evidence he otherwise denies.

The Khazar Myth’s Origins and Misuse: The Khazar hypothesis, popularized by Arthur Koestler’s 1976 book The Thirteenth Tribe, is often weaponized to delegitimize Jewish claims to Israel or portray Ashkenazi Jews as “impostors.” Kraut Daddy’s use of the myth, framed through a Marxist lens, echoes anti-jewish tropes that falsely distinguish “real” Jews (e.g., Sephardi or Mizrahi) from “fake” Ashkenazi Jews. His reliance on this debunked theory, while simultaneously linking Ashkenazi Jews to the Middle East, exposes his inconsistent reasoning.

Why These Contradictions Matter

Kraut Daddy’s contradictions are not mere oversights; they reflect a broader pattern of cherry-picking historical and biblical narratives to fit a preconceived agenda. By misrepresenting the Temple money changers as usurers and equating them with Ashkenazi Jews, he distorts scripture and history to paint Jews as perennial villains. By promoting the Khazar myth while acknowledging Middle Eastern ties, he undermines his own argument, revealing a lack of coherence and reliance on discredited theories. These inconsistencies have real-world implications, as they fuel Anti-Jewish narratives that question Jewish identity and legitimacy.

Genetic Evidence as a Counterpoint: The overwhelming consensus from genetic studies refutes Kraut Daddy’s Khazar claims. Ashkenazi Jews share significant ancestry with other Jewish populations (e.g., Sephardi, Mizrahi) and Levantine groups, such as Palestinians and Druze, confirming their Middle Eastern roots. The absence of Turkic genetic markers in Ashkenazi DNA further debunks the Khazar hypothesis. Kraut Daddy’s failure to engage with this evidence, while contradicting himself by linking Ashkenazi Jews to the Middle East, highlights his selective use of facts.

Biblical and Historical Accuracy: The Temple cleansing narrative has no connection to Ashkenazi Jews or usury. The money changers were facilitating currency exchange for Temple offerings, a necessary function in a diverse pilgrimage economy. Kraut Daddy’s anachronistic and anti-jewish framing ignores this context, as thoroughly addressed in the Ecency blogs cited above.

Conclusion

Kraut Daddy’s X posts reveal a pattern of contradictions that undermineastar his credibility. By claiming first-century Judean money changers were Ashkenazi Jews engaged in usury, he misrepresents biblical texts and commits a historical anachronism, as Ashkenazi Jews did not exist in the first century. Simultaneously, his endorsement of the Khazar myth—claiming Ashkenazi Jews are Turkic with no Middle Eastern ties—clashes with his own assertions linking them to the Levant, contradicting genetic evidence that confirms 40–70% Levantine ancestry. These inconsistencies expose a reliance on debunked theories and distorted narratives, often with anti-jewish undertones. The evidence, from genetic studies to linguistic and cultural data, overwhelmingly supports Ashkenazi Jewish origins in the Middle East and Europe, not the Khazar empire. Kraut Daddy’s claims, riddled with contradictions, fail to withstand scrutiny and serve as a cautionary tale against uncritical acceptance of online narratives.

Call to Action: Engage with credible sources, such as peer-reviewed genetic studies and biblical scholarship, to counter lies. If you encounter Kraut Daddy’s claims on X, share the facts: Ashkenazi Jews have deep Levantine roots, and the Khazar hypothesis is a myth unsupported by evidence.